In this interview, visual artist Razan Al Sarraf talks to Elina Sairanen about her practice, educational background, shares insights into her artistic path and discusses particular series, including The 100 Portrait Series of deceased ISIS members. Al Sarraf is based between Kuwait and Los Angeles and her work focuses on covering the social, cultural and spiritual climate of the Arab world. She graduated with honours from the School of Visual Arts in New York with a BFA in Fine Arts and is currently an MFA candidate at CalArts in Los Angeles.

‘Sheikh Series’

Elina Sairanen: Dear Razan, it’s great to meet you. Could you introduce yourself to our readers?

Razan Al Sarraf: Hi! I’m Razan, born and raised in Kuwait. I have been doing art since I was a child. I did my Bachelor’s in Fine Arts in New York and afterwards spent a couple of years working in the city. I was interning and working with galleries, curating and doing my own studio work. I was supposed to go to Kuwait for a couple of projects for about four months but then COVID-19 hit and I ended up staying there for a year and a half. I was also supposed to do my Master’s at CalArts in California starting last fall, but because of Trump and all the weird new rules with immigration, we ended up being remote and international students had to stay in their countries of origin. I did the first year of my Master’s on Zoom with an incredible 10-hour time difference. Finally this August, I managed to move to California, where I am right now at the beginning of my second year with this programme and hopefully graduating in May.

ES: Wow! How was that, the first year of your MFA on Zoom with such a time difference?

RAS: It was interesting and exhausting, but also fruitful in a very unexpected way. Back in New York, I was making a lot of work about Kuwait; for instance about being from there or dealing with topics I had conflicts with, trying to understand them better through my work. But then something shifted as I was back in Kuwait. I had a few months where I was completely stagnant because I couldn’t understand how to produce or make work about a place that I was currently in when I was used to seeing it from a distance. I was in an interesting, weird ‘in-between’ type of a space, being simultaneously at home but also online in an academic setting in the US. In the end it was great as I got to make ‘hands on’ work – something about Kuwait in Kuwait, something I hadn’t been able to do earlier and also never thought about doing. At the same time, my work greatly benefitted from the eyes, critique and perspective of my faculty and fellow students.

ES: Was it a conscious choice for you to become an artist? Did you always wanted to pursue a career in the arts?

RAS: I was always making art, but I never saw it as a career until I was in high school. I was applying for colleges and while some family members were pushing towards more financially stable choices, I was more interested in seeing what could happen if I focused on fine arts. During my undergrad, I realised that this is definitely something I want to do for the rest of my life: being an artist, but I also have goals of being an educator. Eventually, as I get older, I would like to teach undergraduate and graduate levels both fine arts and art history.

ES: Let’s talk a little bit more about your studies in the US. How was your experience of studying there while coming from Kuwait? How did you find the programme? As we well know, art history has been traditionally written from the perspective of white men with an inherently Western focus or even obsession.

RAS: During my undergraduate years it was quite difficult because I found myself in a conflicting space. I was trying to understand my own clashes and experiences in Kuwait and being an Arab woman and an Arab female body in the West. With that there were a lot of complications that came with language, translation and context. The other problem that I had was that instead of being received openly without predispositions, stereotypes or preconditioned ideas of what I was supposed to be, I ended up making a lot of shortcut works that were more educational because I felt like I had to explain the validity of my experience or my ideas and that I had to provide the context for other people because, as you said, art history is mostly written through the eyes of white Western males. And at the same time, the history of Islamic or Arab art is usually seen from an Oriental perspective. Consequently, I was in a weird space where I felt that I needed to educate these people on where my thoughts were coming from and why they were important. In the end, I did not have enough time to spend on actually thinking about my own issues.

While I was stuck in Kuwait, I was able to think about everything more practically, what I was trying to gain from my work and what I wanted the work to do if I wasn’t in the room. That’s where, and I think we’ll talk about this later also, the hooded figure series started as I was more direct and engaging with myself. With this work, I commented on something I am also experiencing, but also something the Western media is quite obsessed with – the veil, that is. For me, this series is more personal and intimate and definitely more ambiguous, too. While doing this, I was also learning about the power of ambiguity as a resistance to colonisation.

After starting my MFA programme, I decided to think more about what’s important for me and people like me. I think this kind of directness and honesty is what makes it easily translatable as opposed to spoon feeding.

ES: Right, I’m sure many people with similar backgrounds to you will relate to your experiences. Could you elaborate more on your position ‘in between’ cultures, namely Kuwait and America? How do you negotiate that position? And how do you think it’s reflected in your work?

RAS: Indeed, as we talked earlier, in the beginning in the States, there was this pressure to find a common ground between my audience and the content of the work. When I moved back to Kuwait with the intention of showing the work I had made in New York, the reactions I got were less than ideal because most people couldn’t resonate with it. Either the context was different or I was showing them things that they just weren’t interested in.

The ISIS portraits in the US were perceived as ‘interesting’ or ‘controversial’. In Kuwait, the perception was completely different. The series was found ‘unsafe’ and ‘confusing’. For the audience, it didn’t make sense as it was perceived as overly political and people were not appreciating them but favouring different types of work. While I was in Kuwait, I gained a new sense and desire of my work to translate also at home. I also didn’t think at that moment that I could make work that translates well in both places – at least not the same way. That’s the period, maybe about two to three months of stagnation, when I just really couldn’t understand where to place myself. I also couldn’t really understand or couldn’t even figure out what I wanted to talk about in my work because I didn’t know why or for whom I was doing it.

Eventually, I reacted to that by making work about my surroundings. That’s where the video came in: landscape documentary, talking about certain cultural or social issues, concepts I was curious about and experiencing in real time.

After I moved back to the US, another period of stagnation began because now, like the work that I did in Kuwait, is being received very differently. Here, there’s a degree of criticality. There are a lot of whys: why are you doing this? Why is this important for you? Why is this significant to art history? Why is it significant to react in a visual sense? Why painting as opposed to photography? Why video as opposed to performance or sound? Now that I’m back here I’m negotiating these questions and issues — this in-betweenness — working through the confusion and continuously making work to answer those questions.

Not to be a cliché, but I think the power of art is to understand questions that you can’t answer through theory and reading. With art-making, there’s a lot more freedom.

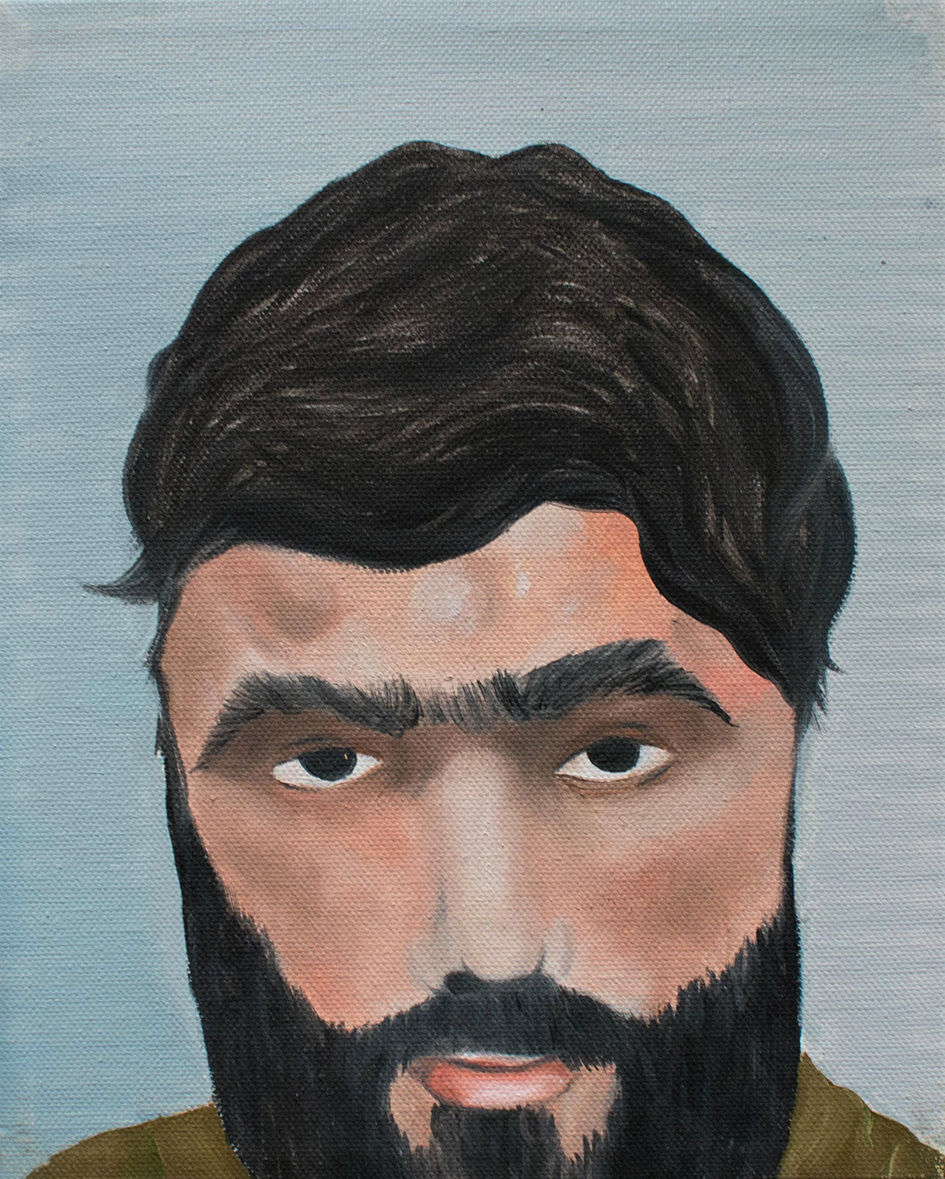

‘The 100 Portraits’

ES: Let’s talk about your so-called ISIS series, The 100 Portraits, unless you are tired of it already. I know that it’s a bit of a recurring theme in your interviews. Maybe you could start by elaborating on how you arrived at the series? How did the idea come about and how did you end up developing it further?

RAS: Sure. The series was created in 2016. I was studying in New York and I was already experiencing slightly traumatising encounters: racism, microaggressions, xenophobia, issues at the airports, etc. During a class, my teacher Peter Hristoff asked us to create a series of paintings with the theme of ‘monsters’. Instead of going with a typical association with monsters – you know those animated figures with sharp teeth and bizarre forms – I took some images of deceased ISIS members that showed up in the media including newspapers and ISIS propaganda. After making the ten initial portraits and putting them up in class, the reactions were what made me want to continue to understand further what the project was. Initially, before the audience knew what they were dealing with exactly, some people found them to look like my possible family members. Others asked me if these were success stories of immigrants coming to the States. Some just focused on the tenderness of the way they were painted – they are oil on canvas and about head-size. They were talking about how beautifully I painted the hair or the skin tones or how I managed to capture their eyes and light.

After mentioning that they were ISIS members, there was this initial switch, a bit of an intense, jarring moment where they were like, oh, how am I supposed to react to this now as I have this system of ideas of what a terrorist is, and now that I’m being confronted by them visually face to face in an academic setting or at a place where we are used to seeing beauty all the time: we are used to seeing things painted for the sake of pleasure and enjoyment. Painting these terrorists was a way of confronting that. Also, it was commenting on the history of portraiture. In the West, it’s seen as a form of idolisation and prestige: painting the wealthy and/or the people you love. Here, you are seeing a portrait of something you’re not supposed to enjoy looking at. What does it mean for you? And what does it mean for the artist to bring forth these images and to confront viewers with them?

I couldn’t really answer all of these questions on the spot, but I was really intrigued, so I continued to paint to see what would happen and showed them in different perspectives and different rooms. The reactions kept changing as did my feelings towards them. I started to almost empathise with them and to understand the psychology of terrorism – what does it mean to be a terrorist? What does it mean to resort to terrorism? What have these people gone through to end up in positions like this, where they feel the safest and most fulfilled in these spaces of violence? In turn, the series brought up questions on community stability, racism, family dynamics, economic situations: all of these people came from places that were broken or unsafe and unfulfilling to their basic human needs.

I found all these questions interesting and I kept painting the portraits until I finished about a hundred. In total, the project lasted a year and a few months. Towards the end I reached a halt where I realised that I’m in a productive space of questioning. This space opened a lot of different perspectives within me as well as a different appreciation towards what painting can do and what making art can do: starting conversations about rather difficult topics. All the connections and conversations I’ve had with people over time are what made it worth it.

To sum up, the reception was quite interesting. Some people thought that I was promoting terrorism while others thought I was raising awareness on something that was way more important than stereotypes, xenophobia and fear-based education.

ES: I think the Western media isn’t always doing such a good job in contextualising terrorism: it’s a sociopolitical issue and not a religious one. Terrorism stems from a multitude of problems such as poverty and lack of inclusion. Considering this, anything that brings more awareness or highlights the context is welcomed. But still, I am wondering if there is a threat of making terrorists seem more human or approachable.

RAS: At first, I don’t think it was intentional to make them more approachable as initially there was this assignment to respond to the idea of monsters. After that title was removed over time and as I removed my preconceptions of how I’m supposed to react to them because of all the harm that they’ve done, my relationship to the portraits changed.

Also, I think it’s important to remember that painting them doesn’t deny or try to hide the damage and the trauma their violence has caused.

I wanted to look at things from a different perspective: to find the nuances in portraying these people and bringing them into a space that is sterile and quite resistant to concepts that aren’t rendered beautiful or are not aesthetically pleasant. There’s something about having these portraits in a gallery space in front of people.

ES: I think the series is powerful from an art historical perspective too. First, it challenges the partly untrue belief that there are no portraits in Islamic art, and second, like you mentioned earlier, it participates in the discussion of who has the right or should be featured in a portrait.

RAS: Yes, the first point is also related to myself as an artist painting portraits and being from a region where images of people are not necessarily very common. Part of my family actually doesn’t have any portraits or images of people in their houses but calligraphy, geometry, Quranic verses or horses. I wanted to address that. And definitely, the series also relates to the idolisation and portraying the wealthy and the important through portraits in the Western tradition as a form of preserving wealth, creating stature and historicising moments of power.

ES: How did your audience react to this series in Kuwait?

RAS: They were confused as to why I was painting them. There were also worries about safety and politics, that showing them in Kuwait could be dangerous for me – which I understand, but that would have also been the point.

ES: Did this type of reaction disappoint you?

RAS: I was kind of expecting it and it didn’t disappoint me as much as it motivated me to want to see Kuwait reaching a point where we’re able to have conversations like this with art. I also know that at least with my generation things can change a bit. I have a strong feeling that we’re going to get to a place where we can be critical about our own politics, culture and traditions.

‘The 100 Portraits’ (detail).

ES: What about your Hooded series? What’s the background story of these works?

RAS: After the ISIS portraits, I needed to stop looking at faces. In terms of the artistic process, I wanted to change the scale of my work. I got rid of brushes and oil paints for a while and put myself into a meditative space painting with water on canvas and then dropping ink and moving it around and seeing where the ink went. The more I did that, the more these random figures emerged within the ink. These shapes are not planned; I didn’t draw them in advance – I didn’t have an idea of wanting to create them before I did. The more I made them, the more the figures came up and I just continued to emphasise them and understand what they were.

Generally, I think my process is just to do something long enough until it makes sense. For me, it’s not as interesting if I already know what I’m doing – then it would just become very robotic.

After painting them, a lot of people thought that they were aesthetically pleasing. Having group critiques during my undergraduate years helped me understand that they were more than just beautiful. Generally, there was a perception that they were landscapes of some sort.

However, when I was physically in the room or my name was mentioned and they saw that I was a visibly Arab woman, the artworks turned into women in niqabs or abayas – that this series is about the veil or about covering, about the mystery of the hidden woman.

As this occurred, I became interested in the way these works are interpreted: depending whether I or my name was associated with them. When I describe this series to other people, I always mention that I didn’t have an intention at first. The intention came out after the work was shared with people. Initially, like I said, it was just a meditative process to detox from the portraits and the violence and intensity of my previous year of painting.

ES: So here comes in what you mentioned before, ambiguity as a form of resistance.

RAS: Yes, because other people were requesting me to define exactly what my intentions were and what the series was supposed to mean to them. I think there’s a lot of power in having the piece explain itself and have the piece change within the perceptions of people who look at it. This has been a controversial topic in art for a long time: we tend to value the artists and their ideas and desires in an artwork more than the actual piece. I understand that. I’m not basing my entire practice on completely ambiguous abstract paintings that other people have to give meaning to. But I also think that this series of paintings, in the scope of all the work that I’ve done, can be enough as a silent moment that was based on a protest and a reaction to the previous piece.

ES: I think it’s not surprising to hear about these veil connotations. The West is quite obsessed with veils and veiling – it has been such a recurring topic in several contemporary art exhibitions of regional art at Western art institutions. How did the audiences who thought the images are veils react when they heard the backstory? Do the discussions on veils tire you?

RAS: There definitely was this academic perspective of having to have meaning and relation. Some people were expecting a direct, almost a literal connection between my heritage and my upbringing to the work I’m making. With that comes a requirement to comment about the veil.

On the contrary, I don’t feel the need to keep explaining the veil to people who are not aware of the region or Kuwait in particular. I also don’t have a strong opinion of it either: it hasn’t affected me personally and I’ve always seen it as a choice that other people have made.

‘In Stillness’ (Hooded Series)

ES: In your newest work, a video titled Seeds after Black Gold you are dealing with Arab futurism and sci-fi. What else could you tell us about it?

RAS: I’m exploring video as a medium. I’ve been quite interested in thinking about where we are going to be in the future, say 20, 50, 100 years from now – especially my native Kuwait. I attempted to make work about those questions and it brought me to do some research about how others were thinking about these concepts. Then, I landed upon Arab futurism, which doesn’t really have a clear definition yet, but it did start in Palestine, where filmmaker Larissa Sansour was thinking about where Palestine could exist outside of conversations of occupation, violence and destruction. She approached the idea of her region and her country existing within a framework that doesn’t exist now – free of the current conversations on Palestine. She made films that were almost hopeful but also realistic about where she would want Palestine to be and where it can be, given its current situation. That’s where sci-fi comes in. There’s the science aspect, meaning this is a possible, possibly real thing that can happen and we have the technology for it. But then there’s the fiction aspect – we’re not there yet because of politics, colonisation or oppression.

I was thinking about that while also watching sci-fi films and TV shows and reading Etel Adnan’s Arab Apocalypse, getting all these ideas of expectations and trying to find a negotiable and realistic idea of where we can be – but also have it be outside of where we are now.

The video I did was the result of that mode of thinking that also meshed with a real life event that I was experiencing – my stepsister getting married. As she was getting ready for marriage, there were all of these beautiful rituals and ceremonies that were happening in preparation for her big day and I became interested in the specificity of all of these rituals and the history behind them. I wanted to understand what they meant and I also wanted to see them within the perspective of sci-fi, because sci-fi draws upon history as much as it does from contemporary practices. Sci-fi also has a way of predicting events and concepts based on the patterns of what came before. In my latest work, I try to bridge the gap between the aforementioned rituals.

At the same time, I would like to talk about the environment and post-oil Kuwait. During my trip back, I was getting to know the country again and meeting with new and different people. I almost felt like a tourist: exploring the desert landscapes, the islands, the underground communities, the traditional family scenes. From there, I came across the rituals. Instead of having them in the context of marriage which I removed because I do not really care about the idea of marriage nor patriarchy, I wanted the woman in the video to perform these rituals and have it be contrasted with a very polluted, trash-ridden outdoor landscape. In the work, she’s basically building up or rebirthing the land outside through her own practices of self-preservation.

The title of the work, Seeds after Black Gold, comes from oil, aka black gold and seeds representing the idea of a rebirth, hope or the starting of new life. The rituals I have filmed are almost identical to what my stepsister was doing, but with some changes. For instance, the box with traditionally expensive items, jewelry and perfumes that represent longevity and blessings, were removed and replaced with seeds. In the film, the protagonist plants them into the land with her love, femininity and power as a woman while the landscape is quite dark: oil pollution, smoke, garbage swamps, and overall death and decay. After these scenes of decay, life reemerges into the frame again, representing hope.